Diamondback 360 Coronary Orbital Atherectomy System (OAS) breaks down calcium build-up in arteries

A new procedure being performed by a Hampton Roads cardiologist could mean the difference between having a stent placed to open up an artery and having open-heart surgery.

Only a few hospitals in the United States are using the Diamondback 360 Coronary Orbital Atherectomy System (OAS), which allows doctors to deploy a tiny device into an artery to reduce built-up calcium. Bon Secours Maryview Medical Center in Portsmouth, Virginia, is the first hospital in the area to use the new cutting-edge technology.

“If it’s used right and it’s used carefully, it could make a big difference,” says Dr. Jayaraman Venkatesan, a cardiologist with Cardiology Associates, a Bon Secours Medical Group specialty practice.

The OAS, created by medical device company Cardiovascular Systems, Inc., was approved by the Federal Drug Administration in October 2013. It treats calcified plaque in arterial vessels throughout the leg and heart in a few minutes of treatment time. The company says its system addresses “many of the limitations” associated with the treatment of vascular and coronary disease.

According to the American Heart Association, some 16.3 million people in the U.S. have been diagnosed with coronary artery disease, or CAD, which is the most common form of heart disease. CAD claims the lives of more than 600,000 Americans each year.

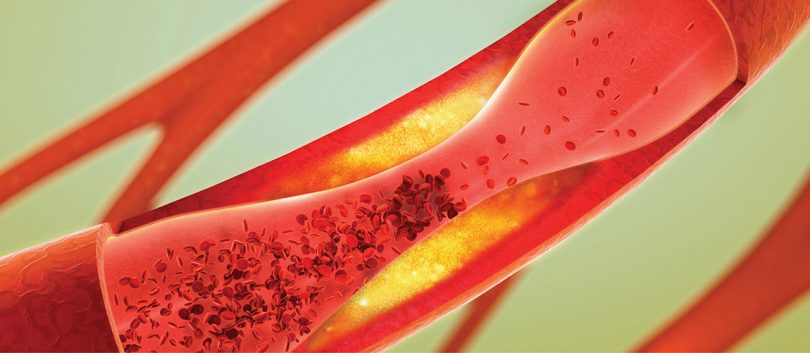

The disease occurs when the arteries that supply oxygen-rich blood and nutrients to the heart muscle become narrowed or blocked by a gradual build-up of what’s called plaque. Plaque is made up of fatty deposits along with calcium, white blood cells and scar tissue. Over time, the plaque collects in the coronary artery walls. Calcium build-up causes blockages to harden and narrow the openings. Conditions such as hypertension and diabetes can accelerate the process.

Treatment is necessary to improve the blood flow through the arteries and increase the supply of oxygen to the heart. After a diagnostic angiogram—an imaging test that deploys dye via a catheter, doctors typically perform an angioplasty—a procedure to restore blood flow through the artery.

During an angioplasty, the doctor uses a small balloon to push the calcium outward to widen the artery. A stent can then be placed to hold open and strengthen the artery to allow for regular blood flow to the heart.

That’s when the OAS procedure may come in. If the calcified plaque is very severe, it can be challenging to safely navigate through the artery in order to deploy the stent, Venkatesan says. The Diamondback 360 device can be used to sand the calcium down, rather than push it away. It uses a rotating 1.25-millimeter diamond-coated crown to clear away the build-up through centrifugal force. The particles are absorbed harmlessly into the bloodstream.

The procedure is intended for those who have severe arterial calcium build-up. Sanding the calcium away allows for better movement through the artery and better placement of a stent. If a stent isn’t inserted correctly, the chance of an artery clogging up is higher.

“This procedure helps to open up the blood vessel a little bit more,” Venkatesan says.

Severe coronary arterial calcium is a vastly underestimated problem in medicine, says David L. Martin, the president of Cardiovascular Systems. It’s a common occurrence and can lead to significant complications—including a substantially higher occurrence of death and major adverse cardiac events.

Patients agree to the OAS procedure knowing that if a stent can’t successfully be placed, it could mean immediate bypass surgery. Having the Diamondback device will enable doctors to more effectively treat calcified arteries, Venkatesan says, and hopefully reduce the chance of more invasive procedures.

Rose Mary Ball, the first (and, so far, only) patient to undergo the new treatment went to Maryview hospital in September with severe chest pains. The 73-year-old Portsmouth woman was having a heart attack. Venkatesan told her about the procedure he was going to try.

“But I didn’t know it was new,” Ball says.

If it didn’t work, the doctor warned, he might have to do a bypass. Fortunately, the procedure was successful, and Venkatesan was able to place two stents. Ball’s artery had been 98 percent blocked. The procedure opened it up, and medication is helping with another blockage.

“I guess I lucked out,” Ball says. “They fixed the problem, and made me all better.”